INTRODUCTION

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a disability that limits an individual’s ability to develop skills in social communication and social interaction [1]. A deficit in social communication is one of the main characteristics shared by individuals with ASD, and many individuals with ASD never develop spoken language [2]. However, many strategies are employed to improve the communication abilities of children with ASD. Developed by Bondy and Frost [3], one such strategy is picture exchange communication system (PECS).

PECS is a means of aided augmentative alternative communication (AAC) that consists of six phases. In the first phase, children with ASD learn to exchange a picture for an item or activity they desire instead of pointing to a symbol to obtain that item or action. Over the course of the six phases, the child is taught to initiate communication by requesting items through discrimination, to respond to questions like “What do you want?”, and, ultimately, to make social comments (e.g. statements of the form “I see+object”). The PECS process helps individuals with communication difficulties to engage in spontaneous communication [4].

Several literature reviews reveal that PECS has been widely used to develop the functional communication skills of individuals with ASD and other developmental disabilities and that PECS is both appropriate and effective for individuals of different ages and ethnicities and with different communication abilities [5–10].

Although several intervention studies have investigated PECS and ASD, no study to date has examined parents’ perceptions of PECS. However, several studies have examined families’ perceptions of AAC in general, and these have used survey, interviews, and focus groups [11–22]. A number of researchers have interviewed parents [13,15,18–20,22] or conducted focus groups [21] to explore their perceptions of AAC. For example, Bailey et al. [13] interviewed six parents regarding the use of AAC devices and identified several themes in their responses: a) school personnel offered AAC training to families; b) caregivers found that AAC devices increased their children’s independence, improved their competency in communication, and provided opportunities; c) the AAC team provided support; d) caregivers found AAC training to be time consuming, especially given that they were responsible for caring for children with disabilities; and e) researchers found problems regarding the portability and dependability of the AAC devices. The authors cited these themes in recommending future research.

Five studies reported a need for families to collaborate with professionals in using their native languages with AAC [15,18–20,22]. For example, Parette et al. [22] interviewed families with different ethnic backgrounds—including “Asian-American,” “Hispanic,” and “European-American”—to examine their perceptions and understanding of AAC. The results revealed that families need information from professionals regarding the use of AAC in their native language and that they are interested in networking with other families with similar needs. Similarly, McCord and Soto [20] interviewed members of four Mexican-American families about their perceptions of AAC. The family members reported that because their conversations with their children were slow and complex when they used AAC devices, they often opted for other methods. After interviewing seven parents and practitioners who used AAC, Lund and Light [18] found that cultural differences were barriers to achieving positive outcomes with AAC. They discovered that the parents found it difficult to develop a communication system in their native language. Moreover, the participants identified other barriers to achieving positive outcomes with AAC, including attitude barriers (e.g. negative attitudes on the part of professionals, society, and children’s peers), technological barriers (e.g. limitations and breakdowns of technology and the difficulty of using technology), and barriers to the delivery of services (e.g. professionals who are limited in their availability and knowledge).

Goldbart and Marshall [15] and Marshall and Goldbart [19] interviewed British families regarding their perceptions of AAC and their lived experiences as parents of children with significant communication disabilities. The parents reported that AAC had strengthened their children’s communication and improved their family lives. In addition, the parents conveyed that they were aware of the influence of society in the lives and experiences of their children.

Another study, conducted by McNaughton et al. [21], used an internet focus group to gain an understanding of the perceptions of seven parents of children who used AAC. Most of the parents reported that they were involved in the selection and use of AAC. In addition, the parents reported that they had encouraged their children to use AAC in multiple environments and with different communication partners.

Five other studies [11,12,14,15,17] used survey methods to examine perceptions of AAC. Angelo et al. [11] surveyed 59 families with children aged 3–12 about their perspectives on AAC. The parents indicated the need for their children to use AAC devices in the community. It is also suggested that parents use trained personnel for instruction, locate advocacy groups, increase their knowledge concerning instructional practices with their children, and obtain funding for the devices and support services. The authors stressed the need for additional parent interviews to provide more in-depth information on parents’ needs.

Herzroni [17] surveyed 74 Israeli parents about their perceptions of AAC. Most of the families reported that AAC improved their children’s speech/language. In addition, some families reported that their children used AAC both at school and at home. In another study, Angelo [12] surveyed 114 families about their perceptions of AAC devices, particularly the consequences and outcomes they perceived in using AAC devices. The results revealed that in 50% of the families, one parent (generally the mother) shouldered most of the responsibility related to the AAC device. Only 25% of the participants reported difficulty using AAC at home.

Calculator [14] compared the perceptions of 182 parents (divided into two groups) of children with Angelman syndrome. The survey focused on the children’s communication systems and their use of and access to AAC devices. Both groups demonstrated a capacity to be successful using high-tech AAC devices and general acceptance of the devices. The researchers recommended additional research into the acceptance of AAC by different stakeholders. Calculator [15] also examined the perceptions of 209 parents of children with Angelman syndrome regarding their children’s use of AAC devices, inquiring about the importance and usefulness of these devices, about the extent to which their children accepted these devices, and the success they achieved using them. The results were similar to those of Calculator [14]: AAC devices were perceived as important, acceptable, and useful.

While most of the studies described above examined AAC in general, no studies have specifically examined parents’ perceptions of PECS, even though PECS is popular and widely used. However, numerous intervention studies in which individuals with ASD were taught to use PECS questioned the social validity and usefulness of PECS; this provides only an individual perspective on parents’ views of PECS. To understand the impact and usefulness of PECS and barriers to its implementation, however, a comprehensive parental view of PECS is necessary. For this reason, this study examined the perceptions of parents on the use of PECS to enhance the communication skills of individuals with ASD and/or other developmental disabilities. It answered the following questions: a) “What do parents know about PECS?” b) What are parents’ perceptions of PECS?”, and c) “What benefits and barriers do parents attribute to PECS?”

METHODS

Participants

Approval from the Human Research Protection Program was obtained before this study was conducted. An email that included a description of, a link to, and access information regarding a survey was sent to administrators of several organizations in the United States, Canada, and Europe. These organizations included professional organizations, parent organizations, and private agencies serving individuals with autism and developmental disabilities. The administrators were asked to forward the email to their membership list of parents and professionals they served who cared for children with ASD and other developmental disabilities. Clicking the survey link, reading the consent page, and accessing the survey implied consent. In addition, individuals who accessed the survey were encouraged to forward it to additional participants. Because this study focused solely on parents’ perceptions of PECS, participants had to have experience with PECS.

The content validity of the survey and the pilot study

Once an initial draft of the survey had been created, four experts in PECS evaluated its content validity. These experts were asked to comment on the clarity and importance of each item and the extent to which the survey avoided words that could generate bias on the basis of gender, race, culture, or ethnicity. The survey was then sent to 20 professionals and parents who used PECS. They were asked to complete the survey and to relay any concerns that they may have had regarding the clarity of the items. The investigator then revised the survey in response to the participants’ concerns. Next, a link to the survey was distributed via an online software platform (Qualtrics®) to several agencies and organizations. Potential participants were informed that the survey would take approximately 10–15 minutes to complete. The survey instrument obtained demographic information and measured four factors: participants’ knowledge of PECS, their use of PECS, the benefits they perceived in using PECS, and barriers they perceived to using PECS.

The demographic items obtained each participant’s age, educational level, employment status, and income. Additional items obtained information on individuals with autism and/or developmental disabilities, including demographic information (e.g. their age and gender) and other information (e.g. their diagnosis).

Each parent rated their knowledge of PECS in the following areas: locating information about PECS, teaching their child to use PECS, and integrating PECS into their home life. They rated their knowledge in each area using 5-point Likert scales that ranged from 1 (Very Important) to 5 (Not at all important). In the usage area, parents provided data on their child’s use of PECS by answering yes-or-no questions. These areas assessed how long the parent had used PECS, their child’s current phase of PECS, and PECS use at home.

Each parent rated the benefits of using PECS in the following areas: how easy PECS was to use, the extent to which PECS had helped their child to develop their communication skills, the extent to which PECS had improved their child’s ability to speak, and how useful they perceived PECS to be for those of all ages, including children and adults. They rated the benefits of PECS in each area using 5-point Likert scales ranging from 1 (Extremely beneficial) to 5 (Extremely not beneficial). Each parent also rated the barriers to using PECS in the following areas: the need to carry a communication book, limited vocabulary choices, limited training opportunities, the time required for training, modifications required to make PECS usable, the cost of PECS, and the need for a communication partner in using PECS. They rated the barriers to using PECS using 5-point Likert scales ranging from 1 (Strongly agree) to 5 (Strongly disagree).

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the demographic characteristics of the parents and their responses to the survey items. The parents were grouped according to education level, annual income, and the phase of PECS their child was currently using. Bivariate tests were then performed to determine whether the groups differed in their knowledge of PECS, their use of PECS, or their perceptions of the benefits of and barriers to using PECS. A chi-square or Fisher’s exact test was then used to compare the groups’ responses to the categorical items, and a t-test (with a Satterthwaite approximation, if appropriate) was used to compare the groups’ responses to the Likert-scale (and thus ordinal) items. Statistical significance was assessed using alpha at 0.05 level, and effect sizes were calculated using (Cramér’s V and Cohen’s d).

RESULTS

Demographics

Forty parents of children with autism and/or developmental disabilities (37 mothers and 3 fathers) participated in the study. Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the parents and their children. The majority of the parents (75.0%) were between 30 and 49 years of age. More than half (67.5%) had earned a college degree or less, while 32.5% had attended graduate school or obtained a professional degree (e.g., a master’s or a doctorate). The majority of the parents (62.5%) had paid jobs, and of these, 42.5% earned less than $60,000 annually and 55.0% earned $60,000 or more annually. The majority of the children were male (75.0%) and younger than 10 years old (62.5%). One–fourth (25.0%) were currently in Phase III or an earlier phase of PECS, while 22.5% were in Phase IV or a later phase.

Descriptive statistics and bivariate test results

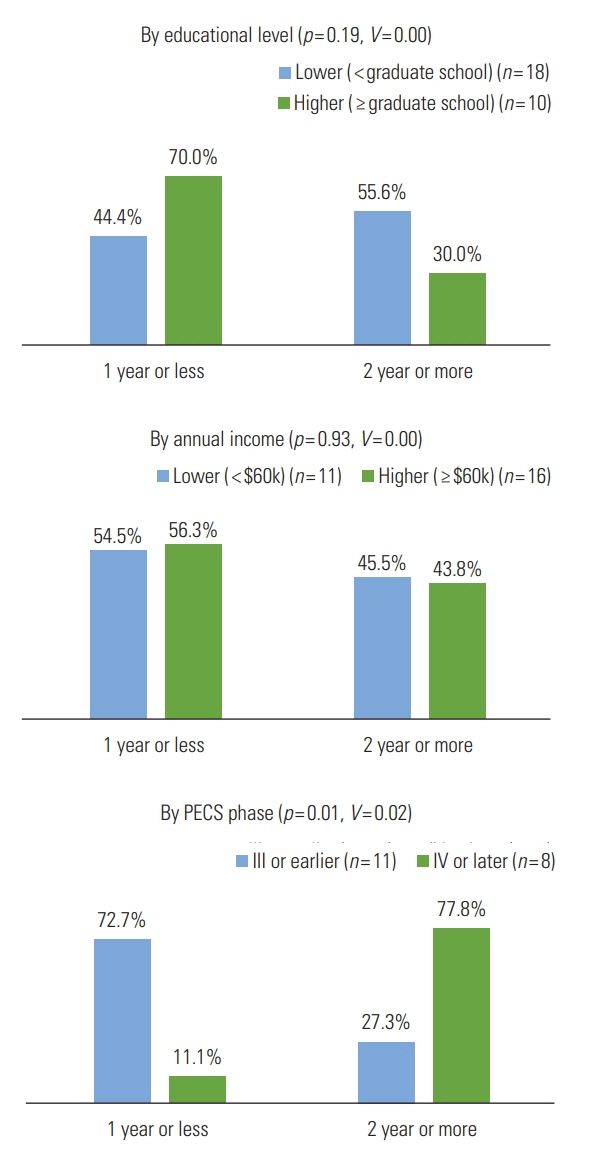

Figure 1 shows how long each parent had used PECS. More than half of the parents (53.6%) had used PECS for one year or less. How long each parent had used PECS was related to neither their education level (χ2 [1]=1.69, p=0.19, Cramer’s V=0.00) nor their income (χ2 [1]=0.01, p=0.93, V=0.00). However, it was significantly related to the phase of PECS that their child was currently in (χ2 [1]=6.74, p<0.01, V=0.02): 77.8% of the children who were currently in Phase IV or a later phase had used PECS for at least two years, while only 27.3% of the children in Phase III or an earlier phase had used PECS for at least two years.

Figure 2 presents each parent’s level of knowledge (i.e. their integration of PECS into their home life). Knowledge was higher for the parents who had earned a graduate degree or more (M=4.80, SD=0.63) than it was for those who had earned a college degree or less (M=4.44, SD=0.70). It was also higher for parents of children in Phase IV or a later phase (M=4.80, SD=0.42) than it was for parents of children in Phase III or an earlier phase (M=4.25, SD=0.89). Although the sizes of these differences (i.e. their effect sizes) ranged from moderate to large, they were not statistically significant at alpha= 0.05—for education (t [26]=1.32, p=0.20, Cohen’s d=0.52) or for phase (t [9.52]=0.16, p=0.14, d=0.83). More interestingly, the parents who earned $60,000 or more annually (M=4.76, SD=0.56) reported significantly greater knowledge than did those who earned less than $60,000 annually (M=4.20, SD= 0.79, t [25]=2.17, p<0.05, d=0.86).

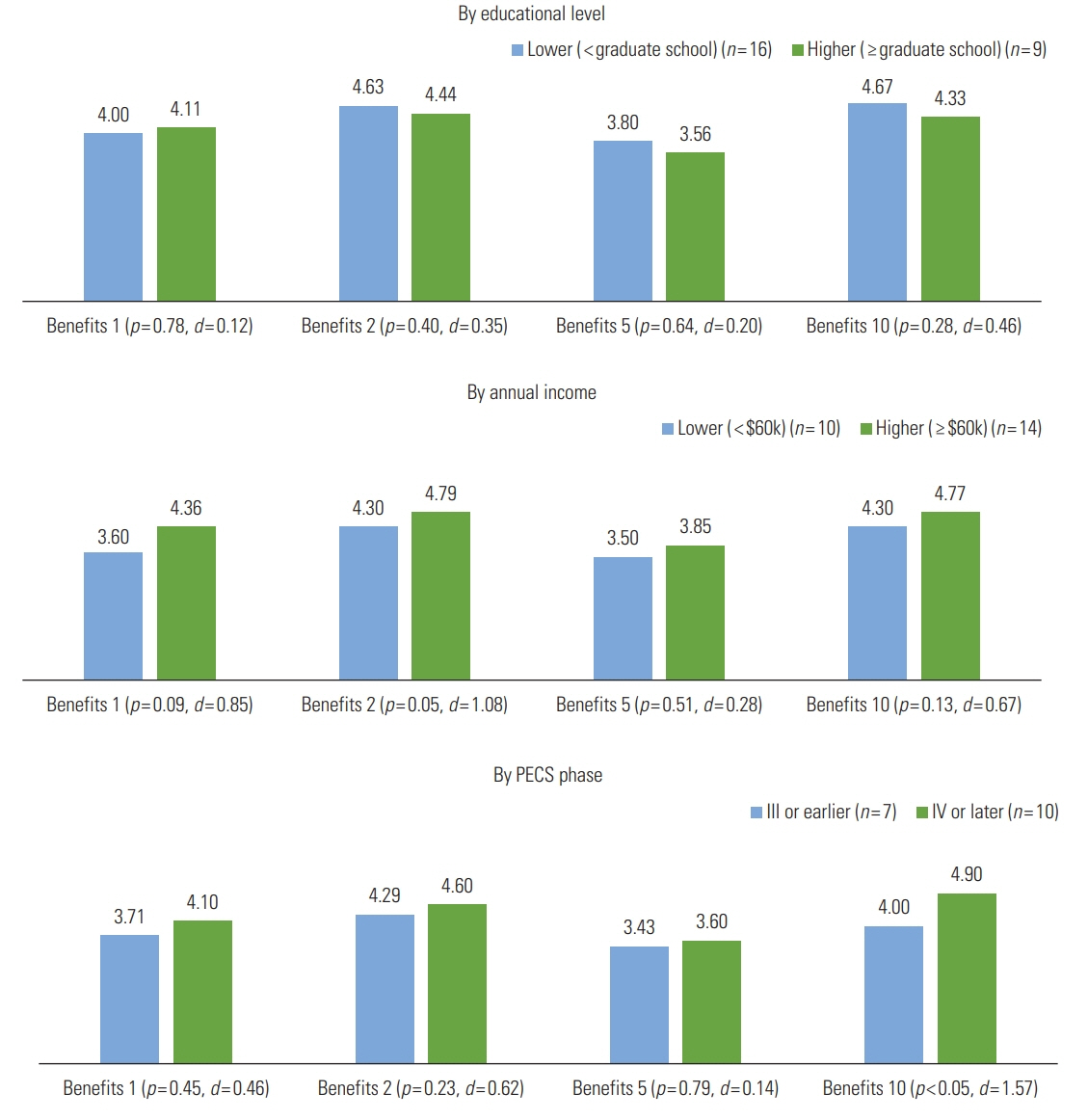

As is shown in Figure 3, in general, parents who had relatively less education, who had higher incomes, and whose children were in later phases of PECS perceived greater benefits to using PECS. The parents who earned $60,000 or more each year (M=4.79, SD=0.43) perceived their children to have developed better communication skills—including skills in requesting and/or commenting—by using PECS than did the parents who earned less than $60,000 annually (M=4.30, SD=0.48, t [22]=2.61, p<0.05, d=1.08). In addition, the parents whose children were currently in Phase IV or a later phase (M=4.90, SD=0.32) were more likely to agree that PECS was useful for individuals of all ages (including those in early childhood and in adulthood) than were the parents whose children were currently in Phase III or an earlier phase (M=4.00, SD=0.82, t [7.27]=2.77, p<0.05, d=1.57).

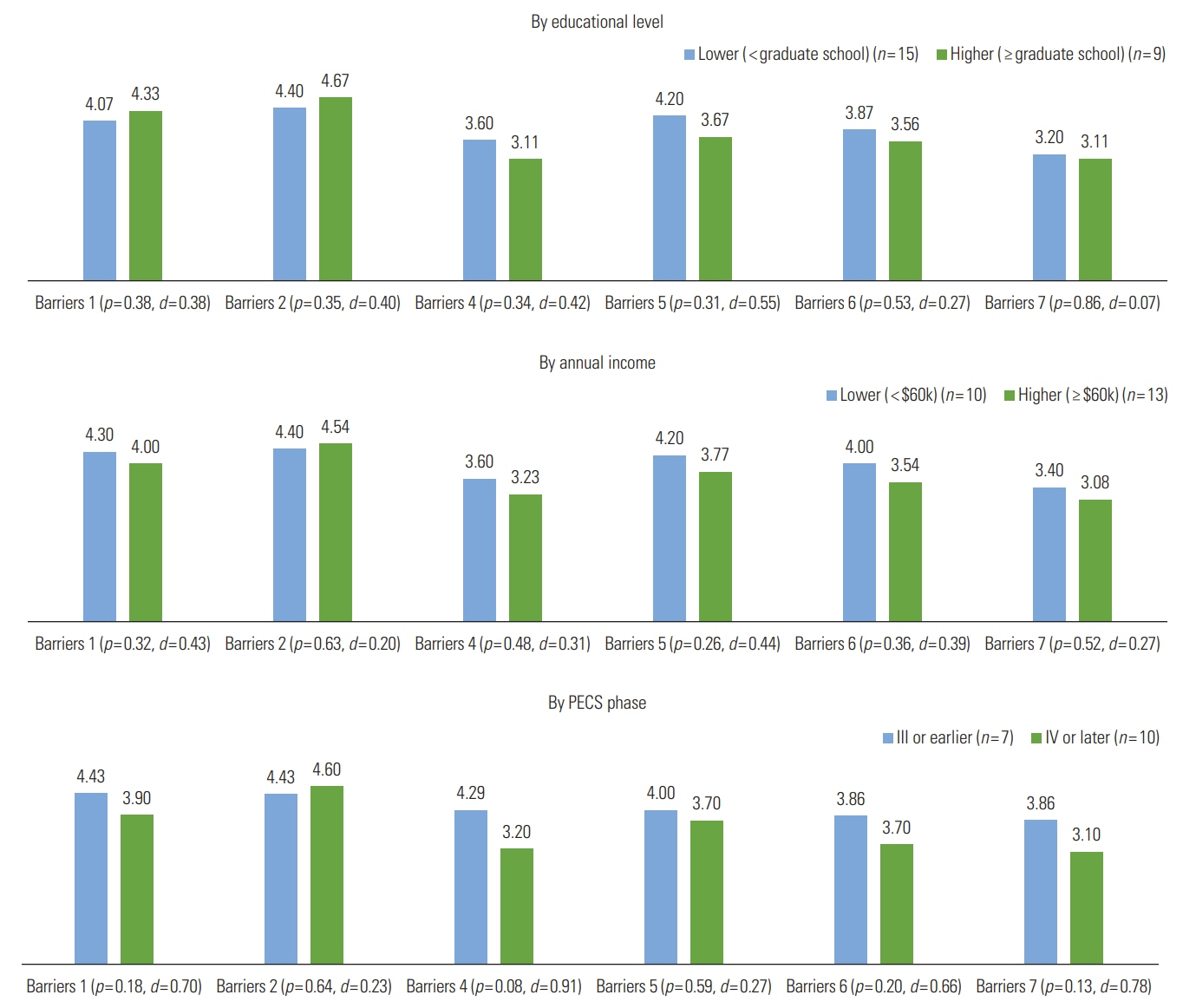

Similarly, parents with lower incomes and whose children were in earlier phases of PECS perceived greater barriers to using PECS (Figure 4). For example, although these results were not significant, parents whose children were in Phase III or an earlier phase differed to moderate degrees from parents whose children were in Phase IV or a later phase in the following areas: the degree to which they perceived it necessary to carry a communication book with limited vocabulary choices (M=4.43, SD=0.79 vs. M=3.90, SD=0.74; t [15]=1.42, p=0.18, d=0.70), the amount of time they perceived necessary for training (M=4.00, SD=1.15 vs. M=3.00, SD=1.05; t [15]=1.85, p=0.08, d=0.91), the cost they perceived to be required (M= 3.86, SD=1.07 vs. M=3.10, SD=1.20; t [15]=1.34, p=0.20, d= 0.66), and the need they perceived for a communication partner in using PECS (M=3.71, SD=1.11 vs. M=2.90, SD= 0.99; t [15]=1.58, p=0.13, d=0.78). In addition, although this result was also not significant, parents who had earned a college degree or less also expressed a greater need for modifications to PECS (M=4.20, SD=0.56) than did parents who had earned a graduate degree or more (M=3.67, SD=1.41, t [9.53]=1.08, p=0.31, d=0.55).

DISCUSSION

This study examined parents’ perceptions of PECS, specifically the knowledge they perceived themselves to have about PECS, the degree to which they perceived themselves to use PECS, the benefits they perceived of using PECS, and the barriers they perceived to using PECS. The results revealed that parents who had earned higher levels of education and/or attained more knowledge of PECS integrated PECS into the home lives of their children to a greater degree than did parents who had earned lower levels of education and/or attained less knowledge of PECS. All of the parents said that PECS was effective in developing the communication skills of their children with ASD and that it was easy to use.

The results agree with those of previous studies that have reported increases in the independence of children who use aided AAC [13,16,17,19]. However, these studies focused on AAC in general, not on PECS specifically. This was the first study to examine parental perceptions of PECS, which is an aided AAC system. These findings are preliminary, however, and more research will be needed to gain a thorough understanding of how parents perceive PECS.

The results revealed that the parents with a graduate-level education or more reported more knowledge of and greater use of PECS than did the parents with a college education or less. The parents with a graduate-level education or more also reported greater success in improving the communication abilities of their children with ASD when they integrated PECS into their home lives. In addition, the parents of children who were in Phase IV or a higher phase expressed greater knowledge of PECS than did the parents of children who were in Phase III or a lower phase, perhaps because the children in more advanced phases had used PECS for longer. These findings are similar to those of Goldbart and Marshall [16] and Marshall and Goldbart [19], which found that parents with high levels of knowledge about AAC understood their children’s needs and integrated AAC into their home lives to improve their children’s communication. However, Parette et al. [22] found that parents lacked knowledge about AAC and thus needed professionals in AAC to aid in the development of their children’s communication. McCord and Soto [20] agreed with the findings of Parette et al. [22], finding that parents need to increase their knowledge of AAC because they play a crucial role in teaching AAC to their children.

The results also revealed that the parents with higher incomes reported more knowledge and use of PECS than did the parents with lower incomes. In addition, they revealed that the parents with higher incomes reported better communication abilities on the part of their children (including in requesting and commenting) than did the parents with lower incomes. However, parents with relatively less education and/or higher incomes and parents whose children were in more advanced phases of PECS perceived greater benefits in using PECS. These results may have been due to the costs of purchasing PECS and attending trainings in PECS.

In general, the parents perceived barriers to using PECS, including the need to carry the PECS book, the amount of time required for training, the costs involved, and the need for a communication partner with whom to use PECS. Some of the barriers that this study identified—the need for training and the costs—were similar to the barriers identified by Bailey et al. [13] and Lund and Light [18].

The majority of the participants in this study were mothers, and the majority of their children were males younger than 10 years old. This is consistent with previous studies conducted to assess parents’ perceptions of AAC. Many of these studies included only mothers [12,15,19] and in many of these studies, the children were younger than 10 years old [15,19]. According to Angelo [12], mothers are more likely to assume greater responsibility for the use of AAC devices. Future studies should explore the role that fathers play in the use of PECS.

Limitations

The limitations of this study include its small sample size, and the education and income levels of the participants. Also, the participants had to have internet access to participate in the study. In addition, this study was internet-based and did not include follow-up interviews to further probe parents’ perceptions; employing methods other than self-administration—such as interviews or focus groups—may have resulted in different responses [15,23]. Another limitation was that the survey did not include open-ended questions, which could have yielded a more complete profile of parents’ perceptions of PECS. To generate a better understanding of how parents perceive PECS, future studies should address these limitations.

CONCLUSIONS

Although a significant body of research has investigated PECS interventions for individuals with ASD, little is known about how parents perceive PECS. However, parents’ perceptions are important to building strong, collaborative relationships between parents and professionals who work with children with ASD. The results of this study suggest that parents find PECS to be effective in improving their children’s communication skills. However, additional research could further support this conclusion.