“Are we…providing them with an equal service?”: Speech-language pathologists’ perceptions of bilingual aphasia assessment of Samoan-English speakers

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

Speech-language pathologists are more often providing services to clients from a different cultural and/or linguistic background from their own. It can be particularly challenging to conduct language assessments with individuals with bilingual aphasia, especially given the limited research in this area. This investigation explored speech-language pathologists’ perspectives on: the challenges that impede the assessment of language in Samoan-English speakers with bilingual aphasia; and the facilitators that support the assessment of language in Samoan-English speakers with bilingual aphasia.

Methods

The study used a qualitative descriptive approach, underpinned by a constructivist paradigm. A focus group was conducted with four speech-language pathologists who had experience working with Samoan-English speakers with bilingual aphasia, including one clinician with extensive knowledge of the Samoan language.

Results

The focus group yielded rich data relevant to the research questions. Analysis revealed 29 codes within eight categories of challenges related to: the Samoan language and culture; the SLP’s background; using interpreters; family involvement; the logistics of the assessment; determining which language(s) to assess; assessment tasks and resources; and obtaining an initial impression of and building rapport with the individual. The analysis also identified 14 codes within five categories of facilitators related to: the SLP’s background; using interpreters; family involvement; determining which language(s) to assess; and assessment tasks and resources.

Conclusions

The investigation provides valuable insights into the experience of conducting language assessments with Samoan-English speakers with bilingual aphasia. The findings may also be useful for informing the delivery of speech-language pathology services to other individuals with bilingual aphasia.

INTRODUCTION

Estimates suggest that more than half of the world’s population is bilingual [1]. In addition, high levels of cross-border migration have led to large numbers of people living in countries other than their country of birth [2]. Speech-language pathologists (SLPs) are increasingly providing post-stroke rehabilitation to people from cultural and/or linguistic backgrounds that are different from their own [3,4]; however, many SLPs report limited competency when working with clients from diverse cultural backgrounds [5]. Providing services to adults with acquired communication disorders, such as bilingual aphasia, can be especially challenging in light of the limited research in this area [1,6,7]. Qualitative studies that explore the perspectives of SLPs who have experience working with people from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds can identify challenges that may impede and facilitators that may inform the clinical management of these individuals [4,8,9].

Bilingual aphasia intervention is a relatively new field and limited research and resources currently exist to guide speech-language pathology practice [10]. The most recent systematic review indicated only 14 studies that had investigated treatment of bilingual aphasia [6], many of which had methodological limitations [7]. Few studies to date have occurred within a clinical setting and have therefore failed to explore the additional complexity of management of this caseload within a real-world setting. Recent surveys of SLPs in the US [11] and Australia [12,13], have highlighted that working with CALD individuals with aphasia is a challenging area of practice for the profession, with clinicians highlighting the need for more research and resources in this area.

One cultural group that, in particular, has received little attention in aphasia research is the Samoan population. The Samoan-English speaking population is a growing demographic group in New Zealand [14]. Stroke, the most common cause of aphasia, occurs at a higher incidence and at a younger age in the New Zealand Pacific population than in New Zealand Europeans [15]. It is, therefore, important for SLPs to improve their understanding of aphasia management for this population. Research in this area may also provide insights that are more broadly relevant to working with other bilingual individuals from CALD backgrounds.

Qualitative description is a useful approach for exploring health disparities in ethnic minorities, such as Samoan-English bilingual adults [16]. Use of this approach allows us to gain in-depth perspectives of one set of key stakeholders involved in assessment of bilingual aphasia. The aims of the present study, therefore, were to explore SLPs’ perspectives on: 1) the challenges that impede the assessment of language in Samoan-English speakers with bilingual aphasia; and 2) the potential facilitators that may assist in the assessment of language in Samoan-English speakers with bilingual aphasia.

METHODS

A qualitative descriptive research approach [16], based on a constructivist paradigm [17], was used to address the study aims. The constructivist paradigm assumes that people construct knowledge through their lived experiences and interactions with others in society; inquiry within this paradigm aims to gain an understanding of these multiple realities [17]. Approval from the relevant ethics committees was obtained prior to commencing the investigation. The team leader of the local district health board cultural support team also provided cultural advice for the study.

Sampling and recruitment

The inclusionary criteria were individuals who: 1) were practicing SLPs (minimum of a bachelor’s degree) with clinical experience working in a health care setting; 2) had self-reported previous experience assessing Samoan-English speakers with bilingual aphasia; and 3) were able to participate in a focus group within the New Zealand city in which the study was conducted. Maximum variation sampling [18], a type of purposeful sampling that involves maximizing the diversity within a small sample, was used, with variation sought for years of speech-language pathology experience. SLPs were recruited through professional special interest groups and the national professional association.

Participants

Six individuals who met the inclusion criteria initially agreed to participate in the study. Two of these participants were unable to complete the investigation. Therefore, four female participants, aged from 24 to 34 years, participated in the focus group. The participants had a range of speech-language pathology experience from less than one year to more than ten years. At the time of the study, the participants worked within three diverse health care settings (i.e., acute care, inpatient rehabilitation, community). One participant had extensive knowledge of the Samoan language. See Table 1 for a summary of the participants’ demographic information.

Data collection

Data was collected during a focus group interview [19], facilitated by the first author. A focus group was chosen for the study because of the interactive nature of this method. The group interaction allowed for the generation of rich data and insights from a small group of participants, with specialized experience in the field that might not necessarily have been obtained had individual interviews been utilized [20]. After explaining the purpose of the focus group, the facilitator led the group in an open discussion, following an interview guide with these topics: experiences with conducting language assessments with Samoan-English speaking clients with bilingual aphasia, challenges that may impede the assessment of language in Samoan-English speaking clients with bilingual aphasia, and facilitators that may support the assessment of language in Samoan-English speaking clients with bilingual aphasia. The focus group session lasted approximately 80 minutes and was videotaped and audiotaped for later transcription [19].

Data analysis

The videotape of the focus group was transcribed verbatim by a research assistant, based on the conventions of Poland [21]. The first author reviewed 100% of the transcripts for accuracy. The transcript was then analyzed inductively, using qualitative content analysis [22] to identify codes and higher-level categories related to the two research aims. The analysis took place over a number of stages. The first stage involved the researcher making reflective notes in a research journal immediately after the focus group. Following this stage, the researcher reviewed the video and the transcript several times to become immersed in the data [22] and to identify data directly addressing the research aims. The researcher then divided the data into meaning units, which were condensed or shortened while preserving their meaning. Similar meaning units were grouped together into codes; followed by grouping of similar codes into categories; and related categories into higher-level categories.

Rigour and reflexivity

The rigour of the study was enhanced through member checking, peer debriefing, and an audit trail [23,24]. Member checking involved sending a summary of the preliminary study findings to the participants and inviting them to contact the researcher, if they had any comments about these results [25]. Peer debriefing entailed multiple discussions between the primary researcher (the first author) and the two co-authors in order to reach consensus regarding the research process and the data analysis. Throughout the study, the first author also maintained an audit trail in a research journal, documenting important details related to the research method and analysis decisions [25].

Reflexivity involves acknowledging that the researchers’ experiences and background may have an impact on the research process [26]. In the present study, the primary researcher (the first author) was a practicing SLP who had previous experience conducting language assessments with Samoan-English speakers with bilingual aphasia. The first author also knew all the SLPs who participated in the focus group. The researcher attempted to deal with these biases by acknowledging and reflecting on them within a research journal and by conducting peer debriefing sessions with the co-authors [23].

RESULTS

Data analysis revealed 30 challenges within eight categories that may impede language assessment with Samoan-English speakers with bilingual aphasia. In addition, the study identified 14 facilitators within five categories that may support language assessment with this population. Results related to challenges are presented below, followed by the findings related to facilitators.

Challenges

SLPs perceived eight categories of challenges related to: 1) the Samoan language and culture; 2) the SLP’s background; 3) using interpreters; 4) family involvement; 5) the logistics of the assessment; 6) determining which language(s) to assess; 7) assessment tasks and resources; and 8) obtaining an initial impression of and building rapport with the individual (Table 2). A description of each category including participant quotations is provided below.

The Samoan language and culture

Participants reported that linguistic differences between Samoan and English made the assessment process more challenging. For example, a participant with knowledge of the Samoan language reported that the language does not “have plurals like you do in English,” does not “have negation like we do in English,” uses a “verb, subject, object” grammatical structure, and that for some English words there is no [direct] Samoan translation (e.g., “hippopotamus”).

Participants also reported that cultural differences in relation to health care and the family’s role when someone is unwell may pose challenges for the SLP: “[I] get a feeling that I’m the health professional and they’re happy for me to do what I’m doing but…they don’t…question it…don’t perhaps see how it is useful…if culturally it’s not as important to them.” One participant with knowledge of the Samoan language and culture stated: “It’s the family’s responsibility to care for [the person’s] needs [in the Samoan culture].” She also indicated that it can be more difficult for a clinician to conduct an assessment with some individuals from a Samoan background because “speech and language therapy is very new…It’s an unheard of profession…Therefore they might not… give you the same…attention…they would give to a doctor.”

The SLP’s background

Participants reported that the assessment process was more challenging when the SLP had limited exposure to and knowledge of the Samoan culture and language such as not knowing about the language’s linguistic structure. SLPs also indicated that having a lack of experience working with bilingual Samoan-English speaking individuals also made it more difficult, with one participant highlighting that this was exacerbated when she was a new graduate with limited experience working with individuals with aphasia: “As a new grad it was my first experience in any assessment with a bilingual person…which added a challenge being new to aphasia and then having someone who was Samoan-speaking on top of that.”

Using interpreters

The use of interpreters during assessments was perceived to present many challenges. SLPs reported that they were often uncertain about the reliability of the results of the assessment, if it was conducted with an interpreter: “No matter how good the interpreters seem…I always…take that assessment with a slight pinch of salt…You’re not quite confident…what you’ve got [written] down is actually how they’re performing…what was interpreted to them or what was interpreted back…was actually what was happening.” For example, the SLPs were uncertain about whether interpreters elaborated on a client’s responses when interpreting them: “You’re never…sure if the interpreter’s giving back exactly what …[the client] has said or forming a sentence around the word [that the client has said].” The SLPs also indicated that they felt they had to listen to what the interpreter said in Samoan to determine if it was of a similar length to the clinician’s utterance. Furthermore, the participants reported that they were often concerned that interpreters were providing the client with additional prompting or extra repetitions of the stimuli: “It’s difficult to know what prompts…the interpreter’s giving.” Another reported challenge was the concern that the clients might perform better than expected the second time through an assessment, if the exact same tasks were administered in both English and Samoan: “You’ve got the test retest problem…They would…be primed. They [would]’ve …heard the questions.”

Other challenges involving interpreters were also identified. One challenge involved the inconsistencies SLPs encountered when working with different interpreters: “The variety of interpreters…some …are very good and some not.” The participants also reported concerns that linguistic features such as the length of words and commands or the grammatical structure of the assessment tasks may be changed as the result of being interpreted into Samoan. Finally, the SLPs indicated that it was more difficult to obtain information about the client’s informal communication and written language abilities when working with interpreters.

Family involvement

The SLPs also identified challenges related to family involvement in the assessment process. For example, the participants reported that it can be difficult if the individual with bilingual aphasia can only speak Samoan post-stroke, while the family can only speak English: “The person has a stroke and they…revert to Samoan but the children don’t speak Samoan…that’s really tricky to deal with.” Another challenge involved managing large numbers of extended family who wanted to be present in the room during the assessment: “I walk into a patient’s room…and there’s about twelve family members… [It] can be quite intimidating…and I’m not sure who would be the spokesperson in a large Samoan family, if there’s sort of cultural [norms] around that.” It was also reported that some families did not want the SLP to use a Samoan interpreter who they were unfamiliar with: “They’re [family]…often wanting to help because they see that the language is a difficulty…You’ve got an interpreter who perhaps is not familiar to the family and they’re thinking…‘We speak Samoan, you’ve brought another Samoan speaker’…You have people saying…‘No at home we say it like this.’” Participants also indicated that families’ perceptions of the individual’s communication impairment sometimes differed from their own, making it more difficult for them to conduct the assessment: “I’ve had so many…even watching [their] interaction I can tell…something is not working and they will turn to me… ‘That’s fine [referring to their communication]’…and you can tell it’s not.”

The logistics of the assessment

Overall, it was perceived that there were some key logistical challenges that influenced the assessment process. One challenge involved the extra time required to organize an assessment when working with an interpreter: “I’ve had situations where the interpreter turns up and the patient’s taken to ECHO [echocardiogram] so we’ve lost that slot; I had to rebook and suddenly I’ve got a patient four or five days [in acute care post-stroke] and I haven’t even done a proper language assessment.” Logistical difficulties related to booking interpreters were also reported to affect the frequency of sessions: “Having to book an interpreter…not being able to be so flexible… The challenge is that you end up only seeing them… a couple of times a week.” Furthermore, the SLPs noted that the times when interpreters were available might not be the most suitable times for the patient (e.g., when he/she is not fatigued). Extra time was also reported to be required to prepare Samoan resources for the assessment or to complete the assessment process: “[I] feel like they do less in the session [than in an assessment session with a monolingual English speaking client]…because…the time it takes.” Finally, the SLPs reported that they may have additional questions about the individual’s Samoan language skills after the interpreter has left and that it may be more difficult to get enough information from the assessment to plan appropriate therapy. One participant highlighted that the various logistical challenges may lead to inequitable service provision for these clients: “Often have that at the back of my mind, ‘Are we…providing them with an equal service?’”

Determining which language(s) to assess

Participants also identified factors that made it more difficult for them to determine which language(s) to assess. They reported that, initially, it could be hard to identify the degree to which each language has been affected by the stroke. One SLP described a case in which she had been told by the health care staff that the Samoan-English individual with aphasia could speak Samoan, but not English after her stroke: “The family had thought…there was hope ‘cause the nurses would say…‘She speaks Samoan.’” This participant stated that it was only when the interpreter reported that the individual was not speaking Samoan, that the SLP could determine that the patient had been using neologisms and that her Samoan language abilities had also been severely affected by her stroke. The SLPs also indicated that it may be difficult to identify which language was more important to the person and the situations in which they used the two languages: “It’s hard establishing what’s their main language… [and] what situations…they use different languages in.”

Assessment tasks and resources

A lack of Samoan assessment tasks and resources was reported to make it more difficult for SLPs to obtain information about clients’ language abilities. Furthermore, participants indicated that formal English assessments may not be culturally or linguistically appropriate: “I remember doing an assessment and it was a question on…wrapping [a present] and the interpreter…let me know that that’s not…commonly done [in Samoan culture] …That [the question] may be…a bit difficult.” Another participant highlighted that it was difficult to complete a word-finding assessment as many of the items appeared to be culturally inappropriate. SLPs added that having to modify formal English assessment tasks to make them more culturally appropriate affected the standardization of the items.

Participants also reported that it can be more difficult to obtain information about the client’s communication activities and areas of participation and to assess reading and writing skills in Samoan. They stated that in general there was less variety in the tasks they could use in an assessment with these individuals compared to an assessment involving a monolingual English speaker.

Obtaining an initial impression of and building rapport with the individual

Obtaining an initial impression of the individual’s communication skills was also identified as being a challenge: “I always find it difficult…with any…bilingual patient or monolingual [patient] in a different language because so much…assessment is based on…[an] overall impression…being able to communicate with someone….It’s always quite difficult to get the overall picture.” In addition, difficulties building rapport with the individuals at the beginning of the assessment were perceived to be more challenging: “Before you do an assessment…you don’t just go in and assess, you usually go in and have a…chat before and …build some rapport…small talk…that’s something that I feel…go[es] out the door.”

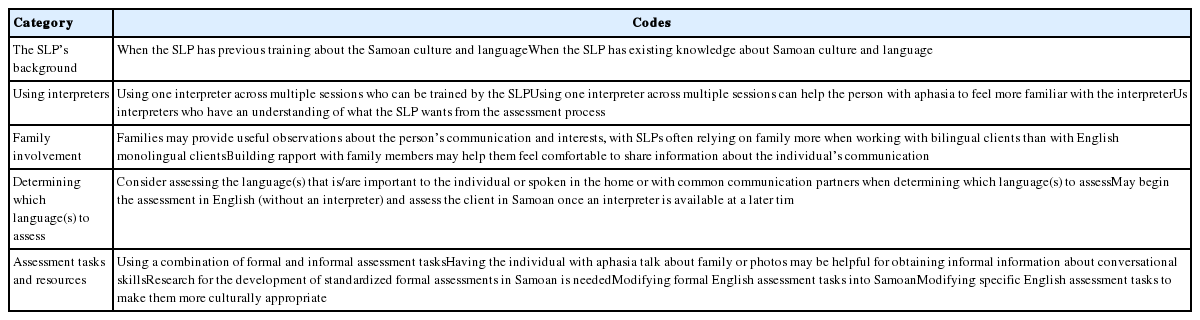

Facilitators

Analysis revealed five categories of facilitators that may support language assessment in Samoan-English speakers with bilingual aphasia. These categories were related to: 1) the SLP’s background; 2) using interpreters; 3) family involvement; 4) determining which language(s) to assess; and 5) assessment tasks and resources (Table 3). Each of these categories is presented below with examples of participant quotations.

Potential facilitators that may assist in language assessment of Samoan-English adults with bilingual aphasia

The SLP’s background

One category involved SLPs having the training and relevant background in the Samoan culture and language. For example, one participant reported, “Looking at assessing someone in Samoan…we actually need to learn all about Samoan language.” Furthermore, the SLP with knowledge of the Samoan language stated, “I think … being able to speak Samoan…is an advantage.”

Using interpreters

Participants identified some facilitators that related to using interpreters that they perceived improved the assessment process. For example, using and training the same interpreter for assessments was identified as being helpful: “Getting to know one interpreter… and training them up in terms of how you want the sessions to be conducted, rather than having lots of different ones…” The use of a consistent interpreter was also reported to be desirable because it enabled the client with aphasia to become more familiar with the person. In addition, participants indicated that it was helpful when interpreters were aware of the importance of informing the SLPs of any linguistic or sound errors made by the clients: “One interpreter…she’s amazing, she’ll even comment on sounds…She [the interpreter] knows what we [SLPs] want.”

Family involvement

Facilitators related to family involvement were also revealed in the investigation. The SLPs indicated that it was useful to build rapport with family members because they could assist in providing further background information about the individual’s Samoan communication skills: “If you can build rapport with the family and the patient,…if they’re …comfortable telling you what they’ve noticed [about the person’s communication]…that gives you a lot of information.” They reported that it was particularly important to develop this relationship when working with individuals with bilingual aphasia: “That relationship’s important with anyone, but specifically when you can’t hear for yourself what’s happening.”

Determining which language(s) to assess

When determining which language(s) to assess, the participants reported that they used strategies such as identifying which language was most important to the person, as well as which language(s) were spoken by their communication partners: “If they’re living at home with their daughter and her children and they only speak English…I’d wanna assess their English.” Participants also reported that it was sometimes useful to begin an assessment in English and then to continue it in Samoan, once an interpreter was available: “You can…start with English because you can do that… [without the interpreter]…and…get a feeling of where they’re at.”

Assessment tasks and resources

Participants reported that it was useful to use a combination of informal and formal tasks during the assessment. For example, the participants reported that it was helpful initially to use informal conversation to elicit a language sample: “There’s often a family photo…I don’t think this is just Samoan families, but [they] are always happy to talk about their family.” Participants also highlighted the need for more research to develop standardized formal assessments in Samoan. Because there were no standardized Samoan measures available, participants indicated they often adapted tasks from English formal assessments such as the Comprehensive Aphasia Test [27] and the Western Aphasia Battery-Revised [WAB-R] [28] into Samoan. Participants reported that they would sometimes attempt to make specific tasks within a formal assessment more culturally and linguistically appropriate for the client: “Occasionally I will change…like…‘Is your last name Smith?’ [on the WAB-R yes-no questions subtest], [to]…a Samoan last name.”

DISCUSSION

The results from the focus group provided valuable insights into SLPs’ perceptions of conducting language assessments with Samoan-English speakers with bilingual aphasia, revealing multiple challenges in addition to a number of potential facilitators. Some challenges and potential facilitators related specifically to working with individuals from a Samoan background. For example, a lack of resources for assessing aphasia in the Samoan-English speaking population was a key challenge indicated by the participants. In addition, the participants felt that some of the stimuli in English standardized measures seemed culturally inappropriate for individuals from a Samoan background. The study also revealed that it is important for SLPs to learn about the language and culture of their Samoan clients prior to conducting an assessment, Samoan clients in particular may have views of health, illness, speech-language pathology, and the family’s role that are different from western perspectives [29].

Some of the challenges and potential facilitators revealed in the investigation may be relevant to CALD populations more generally. For example, in the absence of cultural and linguistic knowledge on the part of the SLP, an interpreter becomes a vital part of the assessment process. However, the study revealed that the use of an interpreter may lead to further challenges such as being uncertain about the reliability of the information obtained during the assessment.

Challenges and potential facilitators involving family were also highlighted within the study. Family roles in the Samoan culture are perceived to be very important [30,31] and a family-centred approach is recommended when working with individuals with aphasia and their relatives [32]. However, the findings from the investigation suggest that a family-centred care approach may be more difficult to implement when assessing individuals with bilingual aphasia. For example, the family and SLP may lack a shared understanding of health and illness. Furthermore, due to the variability of recovery patterns in bilingual aphasia post-stroke [33], some individuals may revert to their native language, possibly leading to communication difficulties if family members do not speak this native language.

A unique finding of this investigation was that the SLPs reported that it was more difficult to build rapport and obtain an initial impression of the communication of clients with bilingual aphasia than with individuals with aphasia who were monolingual English-speakers. In a related finding, a study exploring SLPs’ perspectives on working with Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people found that spending more time developing rapport was beneficial for the therapeutic relationship and patient outcomes [8].

It is interesting to note that the focus group participants discussed at length the issue of choosing which language to assess, even though it is generally recommended that all premorbid languages of a bilingual speaker with aphasia are evaluated [1,34–36]. Some of these concerns may have been related to the multiple logistical challenges of assessment that were identified in the investigation. These challenges included the extensive time taken to plan, prepare resources for, and conduct assessments with bilingual clients.

Clinical implications

A number of implications for clinical practice can be drawn from the study findings. First, there is a clear need for the development of resources for assessing aphasia in Samoan speakers. Although the Bilingual Aphasia Test (BAT) [37] is available in many languages, including the Rarotongan language (Cook Island Maori) [38], no Samoan translation currently exists. Second, the investigation highlighted that it is valuable for clinicians to learn about the language and culture of their Samoan clients prior to conducting an assessment, aligning with the expectations of international speech-language pathology governing bodies [34,35,39]. SLPs have a professional obligation to understand aphasia in bilingual individuals [40] and ideally, a bilingual SLP with a Samoan background would conduct the assessment. However, given this is difficult to achieve, clinicians from a different cultural background to that of their client should at least be encouraged to develop an understanding of the Samoan culture and language. This recommendation could also extend to the training of speech-language pathology students [41].

Other clinical implications may be relevant to working with CALD individuals with bilingual aphasia more generally. For example, training interpreters to become aware of the specific needs of a language assessment was identified as being important in the study. This training could involve a detailed pre- and post-briefing [3,42]. It was also suggested that SLPs could work with the same interpreter over multiple sessions. The SLPs perceived that this potential facilitator could help the interpreter to better understand the SLP’s expectations in addition to allowing the client to become more familiar with the interpreter. These findings link with recommendations from the American Speech-Language Hearing Association [39] when providing services to CALD populations. In addition, the investigation highlights implications in relation to developing rapport with clients with bilingual aphasia. The development of the relationship between the client and the SLP has been identified as a core component of aphasia rehabilitation [43]. The findings from the present investigation suggest that clinicians may need to recognize that building rapport and developing a relationship with their clients with bilingual aphasia may be more difficult and take more time than with monolingual clients. SLPs may also need to focus more on building rapport with family members to obtain valuable information about the individual and his/her communication. In the current investigation, the SLPs reported that they often relied on this information from the family much more than they might for their monolingual English clients Finally, logistical challenges such as the extensive time required to work with interpreters and to prepare for and conduct an assessment may need to be acknowledged by both clinicians and managers when providing services to CALD individuals with bilingual aphasia. By taking into consideration these logistical issues, providers can ensure that these clients receive evidence-based and equitable services.

Strengths and limitations

A key strength of the investigation was that it is one of a limited number of studies that has examined the perceptions of allied health professionals about working with CALD individuals with acquired communication disorders. The study yielded a rich exploration of the topic that has implications for working with Samoan-English and other CALD individuals with bilingual aphasia. One limitation of the study was that the first author knew all the participants and this relationship may have influenced how the participants responded during the focus group interview. Future investigations could consider involving a researcher who is not familiar with the participants to facilitate the focus group discussions. Another study limitation was that the number of participants was at the lower end of the recommended size for a focus group [44]. The use of smaller focus groups can be more appropriate for studies such as this one in which the participants have considerable expertise in a specialized area [44]. At the time of the study, there were a limited number of SLPs who had experience working with Samoan-English speakers with bilingual aphasia in New Zealand. In this investigation, the inclusion of a small number of key informants with expertise in the area, including one individual with extensive knowledge of the Samoan language, resulted in an in-depth exploration of the topic within the group. Future studies in could build on these rich, but preliminary, qualitative descriptive findings by recruiting larger numbers of participants from different geographical regions to further explore this research area.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, this investigation revealed a number of challenges and potential facilitators perceived by SLPs to influence the process of language assessment in Samoan-English speakers with bilingual aphasia. Some of the insights from this study may help SLPs to deliver an “equal service” to Samoan-English and other CALD individuals with bilingual aphasia.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

New Zealand Speech-Language Therapists’ Association Funding Grant, Tavistock Trust Student Aphasia Prize.