Current Perceptions and Unmet Needs of People with Parkinson Disease and their Families

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

A new diagnosis of Parkinson disease (PD) occurs every nine minutes in the United States. It is a multimodality neurogenic disorder whose prevalence is expected to only increase worldwide in the coming decades. Therefore, a systematic examination of the current perception of PD symptoms and the different unmet needs of people with PD and their families can allow healthcare professionals to design more effective education, awareness, and management programs. The current study examined perceptions of different PD-related symptoms among individuals with PD and care partners (including spouses and family members) living in different communities of the United States (including Oklahoma and surrounding regions).

Methods

The study included 39 participants with PD and 11 care partners based in four states (including Arkansas, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas).

Results

Findings indicated that participants with PD and care partners more frequently reported motor symptoms associated with PD than nonmotor and communication symptoms. In addition, specific to unmet needs, both groups reported the need for specialized services and educational resources related to PD symptoms in their respective communities.

Conclusions

Overall, there is a need for more widespread education and access to specialized services specific to PD. Overall, findings from the study will help create more effective service delivery programs for individuals with PD and their families in different communities.

INTRODUCTION

Overview of PD

According to the American Parkinson Disease Association [1], a new individual is diagnosed with Parkinson disease (PD) every nine minutes. Approximately one million people are currently living with PD in the United States. Due to its progressive and degenerative nature, people with PD have a huge social, emotional, and financial burden. It is a multimodality disorder characterized by motor, including physical and speech-related changes and nonmotor symptoms [2,3,4].

The present study examined the current perceptions of different symptoms and existing unmet needs of people with PD and their primary care partners based in Arkansas, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas. The existing literature includes the interchangeable use of “caregiver,” “care partner,” and “communication partner” to represent individuals who may be directly involved with the care and treatment planning of people with PD. The following sections summarize the existing perceptions in the PD community regarding different PD symptoms, current unmet needs, barriers to healthcare services for individuals with PD and their families, and the impact of PD symptoms of QOL in individuals with PD.

Knowledge and perceptions of PD symptoms

Communication is essential for functioning successfully daily, but it is also related to one’s feelings about self and others’ reactions. Changes in speech and voice can often be one of some individual’s earliest indicators of PD. For example, Ho et al. [5] reported about 73.5% of participants had a range of speech symptoms assessed by two trained speech-language pathologists (SLPs). However, limited studies have examined the self-reported effects of PD on speech, voice, language, and communication among participants with PD [5–9].

In one of the earlier studies, Haberman [8] reported the experiences of 16 participants with PD. The authors reported several themes, including different financial and emotional demands of the illness, challenges of a changing body with the onset of different motor symptoms, changes in roles and responsibilities following the PD diagnosis, gradual loss of independence, including not being able to drive as well as the process of gaining formal knowledge about the symptoms and progression of PD [8]. In a different study, Miller and his colleagues interviewed 37 participants with PD about their self-perceived changes more directly in their communication and speech [6]. Most participants self-reported experiencing one or more of the following themes: difficulties during conversations, deterioration in speech intelligibility, the slow rate of speech, increased speaker effort to maintain intelligible speech, and impact on one’s participation in daily activities.

A separate study reported a negative impact on one’s communication secondary to PD by 104 participants with PD and 45 communication partners based in the United Kingdom [9]. Both participants with PD and communication partners indicated a negative impact on communication before and after PD diagnosis. Similar reports of self-reported changes in voice and communication among participants with PD were reported by Schalling et al [7]. The study included 188 participants with PD in Sweden, with 92.5% reporting at least one communication-related symptom. Out of these participants, only 42% had received speech therapy services. The changes were not limited to voice and communication, as 40% of the participants reported the presence of dysphagia. However, only 20.5% had received a swallowing assessment. Overall, approximately one-third of the participants with PD reported a negative impact on communication participation secondary to PD. The authors emphasized the involvement of communication partners in future treatment programs and educating people with PD and their families about the possible healthcare and therapy services available for people with PD [7].

Researchers have also examined awareness of nonmotor symptoms of PD among participants with PD and their care partners. For example, Cheon et al. [10] with examined awareness of PD nonmotor symptoms among 74 participants with PD and 54 care partners (i.e., family members) based in South Korea. The authors used the Korean version of the Nonmotor Symptoms Questionnaire (NMSQuest study) with 30 nonmotor symptoms. All participants were within the mild-moderate disease severity based on the H-Y stage, and the average duration of PD symptoms was about 6.4 years. The mean ages of the PD and care partner groups were 64.9 years and 50.6 years, respectively. Participants with PD most frequently reported nocturia (67.6%), followed by restless legs, constipation, dizziness, memory disturbance, and feelings of sadness. In contrast, delusions, visual hallucinations, and bowel incontinence were the three least frequent nonmotor symptoms reported by participants with PD.

Comparing symptoms by the two respondent groups, the participants with PD typically reported 12 symptoms. In comparison, the care partners reported an average of seven symptoms for their loved ones with PD. However, there were no associations between the number of PD nonmotor symptoms and age, stage of the H-Y scale, or disease duration. The authors concluded that both participants with PD and their care partners were unaware of the different nonmotor symptoms of PD Cheon et al [10]. Approximately 37.8% of participants did not know any nonmotor symptoms on the checklist. In conclusion, the authors suggested that a more widespread effort is needed to improve the knowledge and awareness regarding different aspects of PD among people with PD and their families [10].

Unmet needs of PD

Parkinson disease affects a person’s functioning, including possible loss of social, physical, emotional, and financial resources. Therefore, it is important to understand the unmet needs and ways to educate and provide the necessary and relevant resources to people with PD and their families. A study by Buetow, Giddings, Williams, and Nayar [11] discussed the perceived unmet needs of individuals with PD living in New Zealand. The authors concluded that people with PD may not always have access to PD-specific healthcare professionals in their area, which is a major unmet need for the PD community. In a different study by Cheon et al. [10], more than 60% of participants with PD and their family members in South Korea responded that they wanted to learn more about PD. However, half of them reported not having access to reliable information. Therefore, the authors concluded that more widespread community education and access to reliable and most recent health information could benefit the PD community.

A year later, Hatano and his colleagues [12] discussed the unmet needs of individuals with PD based in Tokyo, Japan. The study included 132 participants in stages I–III of PD and 51 family members of individuals in stages IV–V of PD. Data were collected through a 20-item questionnaire-based interview. The authors discussed the unmet needs of the participants into three categories: lack of benefits from antiparkinsonian agents for managing nonmotor PD symptoms, not as many benefits from PD medications specific to their motor symptoms, and a need for better mutual communication between physicians and people with PD. The study concluded that addressing the unmet needs of people with PD can help improve the quality of life (QOL) of people with PD.

More recently, van der Eijk et al. [13], discussed some unmet needs of participants with PD based within the United States and Canada. The study included 20 Parkinson Centres of Excellence participants in these two countries. Each center included 50 participants with PD who completed the Patient Centeredness Questionnaire for PD [14]. The study concluded that the individuals with PD experienced a lack of collaboration with healthcare professionals and were often under-informed about their critical care needs.

Similar reports of lack of knowledge and insufficient resources for people with PD based in Germany were also reported by Jost and Bausch [15]. A total of 4,485 participants with PD from different regions of Germany participated in the questionnaire. The authors reported a lack of information among participants with PD regarding different PD-related symptoms. Overall, people with PD desired to gain more information about effectively identifying and managing the side effects of their PD medications.

Most recently, Lee et al. [16] reported the unmet needs of participants with PD based in South Korea. One hundred ninety-one participants with PD completed paper-based questionnaires, including the Non-motor Symptoms Questionnaire (NMSQuest), a revised version of the Schwab and England Activities of Daily Living Scale (SE-ADL), and an unmet needs questionnaire. Results indicated that females with PD and participants with relatively severe nonmotor PD symptoms were likely to have unmet needs compared to other participants with PD. In addition, the authors suggested possible ways to facilitate more effective treatment interventions for people with PD. These included providing community support and resources, tailored care in different settings, and easier access to other healthcare professionals, which healthcare professionals are currently working with people with PD and their families consider.

In summary, the studies mentioned above indicated several unmet needs, including effective management of medications and limited knowledge about possible side effects of PD medications. Further, the studies reported a lack of collaboration between healthcare professionals and unmet needs regarding the standard of care that, in turn, may adversely impact the daily functioning of people with PD and their primary caregivers or family members.

Quality of life perceptions of participants with PD

Quality of life (QOL) is a multidimensional concept that includes physical, psychosocial, and emotional functioning. Researchers have used QOL and well-being interchangeably [17]. Previous literature has affirmed concerns about factors affecting the QOL of individuals with PD. Participants with PD and their family members reported higher levels of burden, increased levels of disability, and possible changes in self-identity, all leading to substantial effects on the QOL of individuals with PD and family members. In addition, individuals with PD who were better able to control their PD symptoms were perceived to have better well-being when compared to their spouses [18]. However, no special relationship has been discovered between the well-being of individuals with PD and their family members.

Some studies have specifically looked at possible gender differences regarding the effects of QOL on one’s levels of functioning. For example, studies have reported that for women diagnosed with PD, the symptoms affect their QOL and their families. Specifically, Caap-Ahlgren and her colleagues [19] reported symptoms such as hypokinesia as a major barrier that limited female participants with PD from completing daily tasks. In addition, more recent studies have researched the impact of non-motor symptoms on health-related and perceived QOL. For example, Santos-Garcia and de la Fuente-Fernandez [20]. Associated higher scores on the Non-Motor Symptoms Scale (NMSS) [21] for participants with PD with relatively poorer QOL. In conclusion, previous research has shown a direct impact of non-motor symptoms on health-related and perceived QOL among individuals with PD.

Caregiver-related perceptions and experiences

Regarding family members of individuals with PD, anxiety, and depression are more frequent than expected in their age groups [22]. It is indicated that there is a relationship between family member’s anxiety and depression and their family member’s disease status and progression. Due to the magnitude of symptoms related to PD, family members can feel the weight of caring for their loved ones with PD. Research has suggested that family members of people with PD felt like they were living with the disease themselves. The role of caregiving was a completely unplanned journey. The family members reported a shift in their relationship with their loved ones with PD before and after the diagnosis [23]. Family members also experienced an overall burden on their emotional and physical health [24]. Although previous research has been conducted to examine caregiver’s perspectives, more research and information are needed to understand this group’s current unmet needs better.

Prior studies have discussed with impact of PD impact on individual’s QOL and family members. For example, people may experience social isolation, financial burden, and emotional and psychological symptoms. However, to the best of our knowledge, no to limited information is currently available regarding the current level of knowledge and unmet needs of the PD community in some of the rural regions of the United States, including Arkansas, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas. According to the Parkinson’s Foundation [25], more than 80,000 people are diagnosed with PD in these four states alone. Therefore, based on the current World Health Organization’s objective of patient-centered care, we aimed to examine the current perceptions regarding PD-related symptoms among individuals with PD living and their primary care partners (including spouses or other family members) within these geographical regions. The current study uses the term care partner instead of caregivers or spouses to include a variety of individuals who may be active partners in caring for people with PD. In addition, we examined the different met and unmet needs of the PD community as reported by these groups, including individuals with PD and their care partners (including spouses and family members).

The main research questions of the current study were as follows:

Research Question 1: What were some current perceptions regarding the PD-related symptoms among individuals with PD and care partners (including spouses and family members) living in Oklahoma and surrounding states (including Texas, Arkansas, and Kansas)?

Research Question 2: What were some current unmet needs among individuals with PD and care partners (including spouses and family members) living in Oklahoma and surrounding states?

Research Question 3: What were the effects of PD symptoms on the QOL of participants with PD and the QOL of care partners based in Oklahoma and surrounding states?

METHODS

Collection sites and modes of surveys

The study had an online format and was approved by the Institution Review Board before data collection. Members of different PD support groups in Oklahoma, Arkansas, Texas, and Kansas were emailed the study flyers from June to September 2020. In addition, the second author personally contacted different PD support groups, speech-language pathologists, and healthcare professionals working with individuals with PD via emails and phone calls to share study details. Interested individuals with PD and care partners first completed the online informed consent, a brief demographic questionnaire, and a short depression and mental health screening.

Participants with PD

The current study included two primary groups-individuals with PD and care partners. Thirty-nine participants completed the surveys, including 27 people with PD and 12 care partners (spouses or other adult relatives) based in Oklahoma, Texas, and Kansas. All participants with PD had a self-reported diagnosis of PD and self-reported visual and reading abilities adequate to qualify for participation in an online survey. Care partners included spouses, adult children, or relatives of individuals with PD. They also self-reported visual and reading abilities adequate to complete an online survey. Specific to participant’s locations, 40% were based in Texas, 35% were based in Oklahoma, 5% were based in Kansas, and 20% of participant’s location was unknown during study participation.

The age of participants with PD ranged from 58 to 87 years old. These included 13 males and 13 females; one participant did not disclose their gender. The participants represented an almost homogenous group, with 38 out of 39 reporting Caucasian/White ethnicity. Some of the participants reported co-morbid medical conditions, including high levels of cholesterol (19%), osteoporosis (14.3%), diabetes (9.5%), high blood pressure (9.5%), and osteoarthritis (9.5%).

Specific to participant’s educational background with PD, six reported high school level education, three reported vocational training/associate degree, ten reported an undergraduate degree, five reported a graduate degree, and three reported a doctoral degree. Next, about 81% (n=22) of the PD participants reported being retired during study participation. Two additional participants reported being on disability, and the remaining three reported working part-time, volunteering, or being unemployed during study participation.

The authors determined the severity of the PD symptoms based on self-reports from participants on a 6-point Likert scale (very mild, mild, moderate, moderate-severe, and severe). Higher scores were indicative of greater PD severity. Results indicated that 14 participants self-reported mild severity, nine reported moderate, and four reported moderate-severe PD at the time of participation. In addition to their PD symptoms, 15 participants self-reported stable progression, six reported progressive trends, and one reported a rapidly progressive PD. In contrast, five participants with PD did not know the specific pattern of their disease progression. In addition, five participants self-reported having DBS, while the remaining 22 had no history of neurosurgery to manage their PD symptoms.

Care partners

The study included 12 care partners (Males=2; Females=10) aged 55–91 years. Half of the care partners reported being spouses of people with PD. The remaining half were either family members or did not indicate their specific relationship with the person with PD. Regarding the educational status of the care partners, three reported a vocational degree/associate degree, one reported an undergraduate degree, six reported a graduate degree, and two reported a doctoral degree. Specific to work status, six care partners were retired. Three additional participants worked part-time, and one worked full-time at study participation. Finally, specific to the medical history of care partners, most self-reported anxiety, type 2 diabetes, and prior history of surgeries.

Mental health and depression screening

All PD and care partners completed an online mental health and depression screening [26]. Twenty-six participants with PD completed the survey, with 74% of participants (n=20) indicating a score of 2 or more on the depression scale, indicating the possible presence of depression. Among the care partners, twelve of the 13 completed the mental health screening, and 69% (n=9) of these participants scored a 2 or greater on the screening, indicating possible depression.

Study measures

The current study included modifications of existing surveys [2,6,10,27] with that were related to perceptions of PD symptoms, current needs, and the possible impact of PD on the QOL of participants with PD and care partners. All participants completed four surveys on Qualtrics. The surveys included a symptom checklist to indicate their PD symptoms or those noted in their loved one with PD, currently accessed services, unmet needs specific to PD, rankings of their unmet needs, and QOL ratings.

RESULTS

Perceptions of PD symptoms by participants with PD and care partners

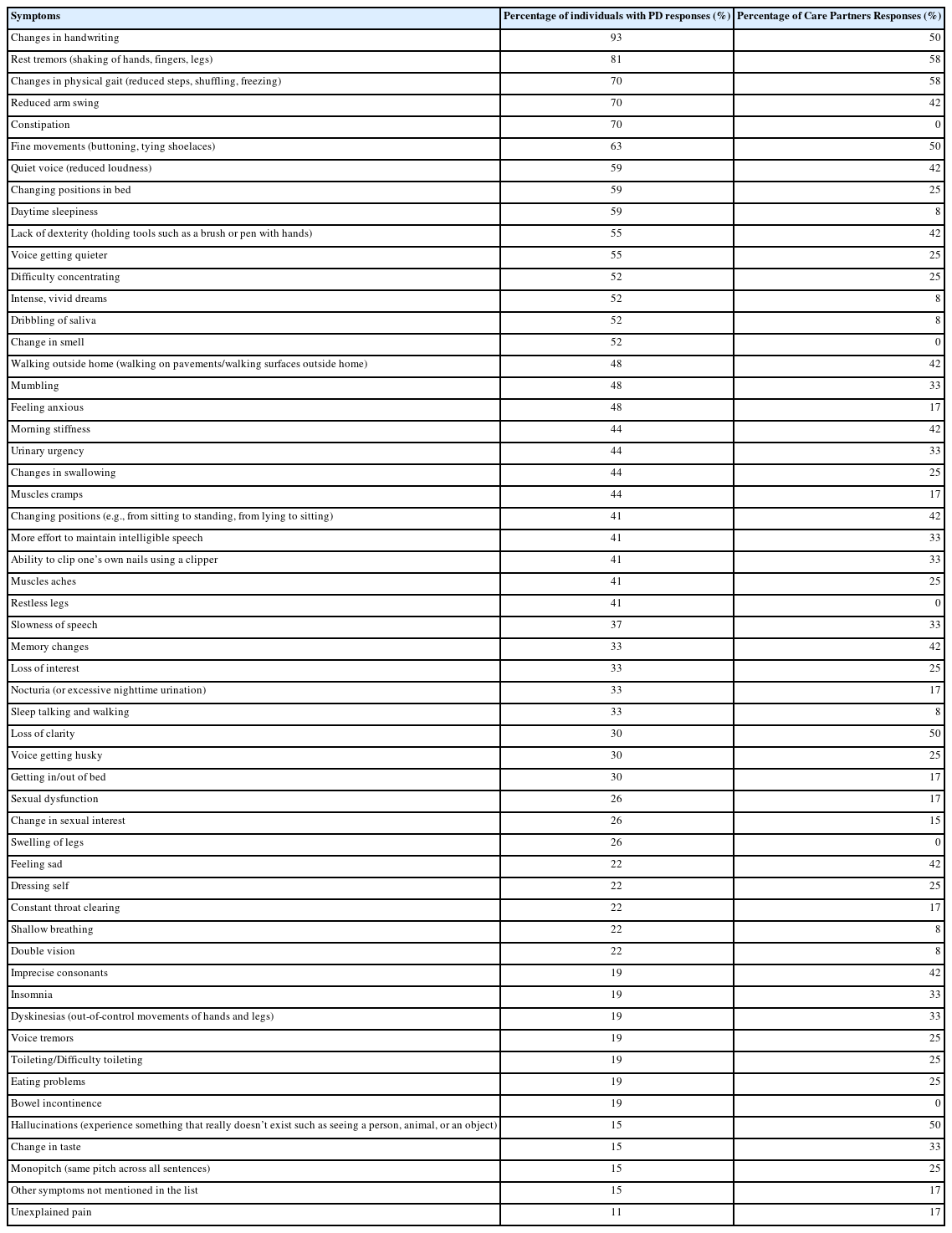

The current study examined the self-awareness of different PD symptoms among individuals with PD. Results indicated that the most commonly self-reported symptoms among participants with PD were changes in handwriting (n=25; 93%), followed by rest tremors (n=22; 81%), and other motor symptoms such as changes in physical gait and reduced arm swing (each with n=19; or 70%). In addition, among the three major domains of symptoms (motor, non-motor, and speech and communication), participants with PD self-reported a relatively greater number of motor symptoms when compared to non-motor, speech, and cognitive symptoms.

Like participants with PD, all care partners completed a survey about the symptoms they noticed in their loved ones diagnosed with PD. The most observed symptoms were rest tremors and changes in physical gait (n=7; 58%), followed by difficulties in performing fine movements (such as buttoning), changes in handwriting, loss of clarity, and hallucinations (each category with six responses; 50%). However, in contrast to participants with PD, the care partners reported a relatively smaller number of motor and nonmotor symptoms among their loved ones. Specifically, only 42% of participants reported non-motor symptoms such as memory changes, orthostatic hypotension, and emotions of sadness in their family members with PD. Table 1 includes the summary of PD symptoms by participants with PD and care partners in percentages.

Access to service delivery reported by participants with PD

In addition to the survey of PD-related symptoms, all participants with PD completed a survey about the current healthcare services they either have accessed in the past or may have access to at the time of study participation. The survey included a list of healthcare and community services, including physical therapy, neurological care, speech therapy, and counseling. Based on the survey results, the top three services that participants with PD accessed were pharmacy (n=9; 70%), neurological care (n=17; 63%), and physical therapy (n=15; 56%). In addition, like the participants with PD, all care partners completed a survey about different healthcare and community services accessed by their family members. The three most common services family members reported for their loved ones with PD included neurology (n=7; 58%), followed by the pharmacy (n=6; 50%), physical therapy/exercise groups, and speech therapy (n=4; 33%). Table 2 summarizes the survey responses of current healthcare and community services accessed by participants with PD and those reported by the care partners.

Unmet needs of the PD community

In addition to the survey about access to PD-related services, all participants with PD completed a separate survey about their current unmet needs. The most common unmet need for participants with PD was vacationing and travel tips (n=10; 37%), followed by implementing an exercise regime or adapting a regime to fit personal needs (n=9; 33%). Additionally, other unmet needs included identifying and accessing resources for the future, effective strategies to manage driving, fatigue, tremor/gait/balance problems, driving, and safety in the home environment.

Like participants with PD, the care partners also reported the unmet needs specific to their loved ones with PD. The most unmet need reported by care partners was vision changes/issues (n=4; 33%). In addition, compared to the participants with PD, about 25% (n=3) of the care partners reported common medication side effects, legal issues, memory, problem-solving, role changes, and services to address apathy secondary to PD also being currently unmet. In contrast, care partners did not select some areas, such as nutritional changes, work transition, and advocacy issues. It is possible that some categories did not apply to the specific needs of their loved ones with PD. Alternatively, they may not have known that these areas were directly related to PD. Table 3 summarizes the unmet needs responses by participants with PD and care partners.

Summary of Unmet Needs Reported by Participants with Parkinson Disease (PD) and Care Partners in Percentages (%)

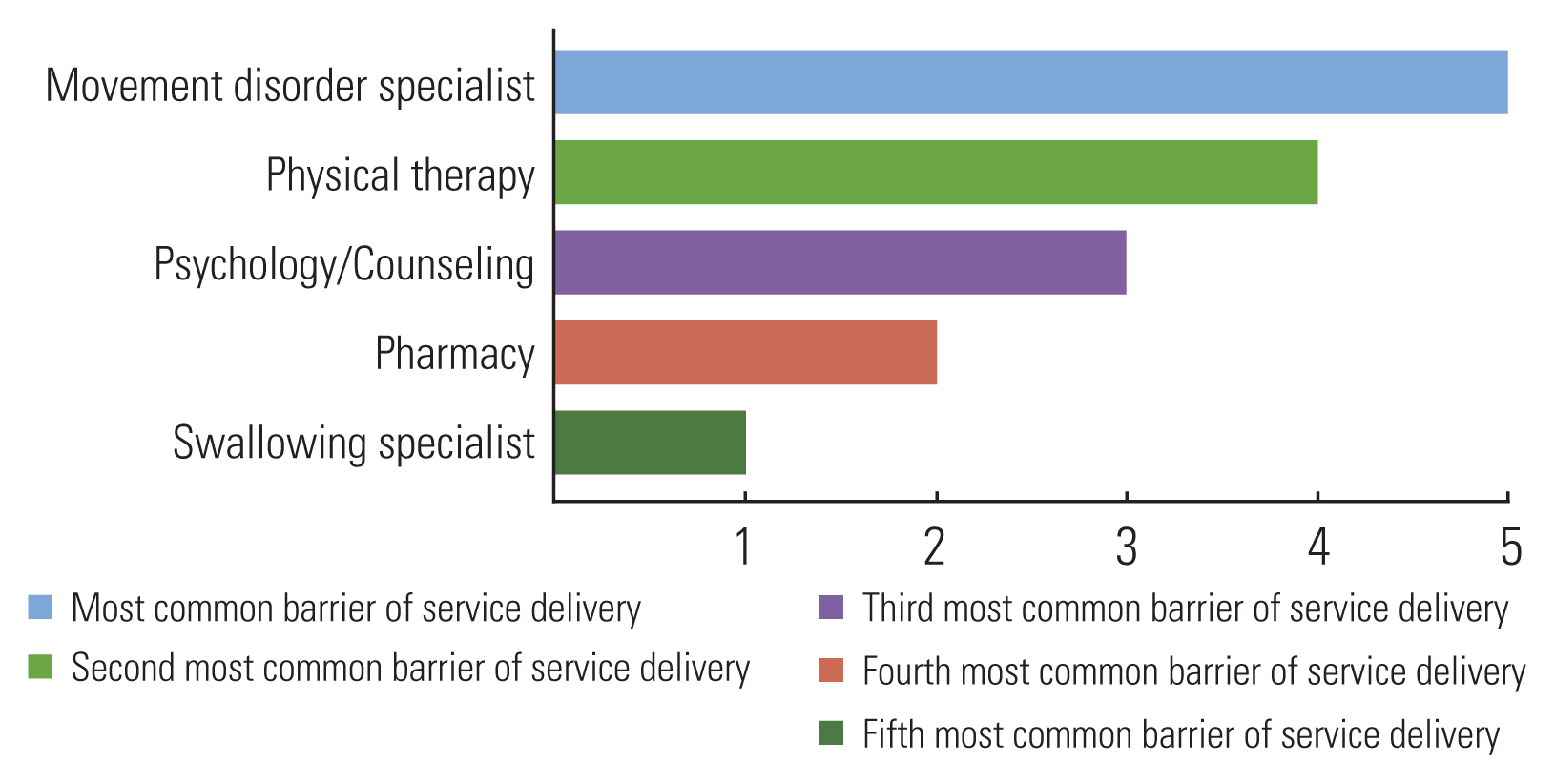

Additionally, the study asked all participants to rank five of their unmet needs. The survey included 15 services for assessing, caring for, and managing people with PD. Among the different services, access to a Movement Disorders Specialist, a Neurology clinic, participation in clinical trials related to PD, nutrition-related education, and physical were listed as of the most frequent unmet needs for the PD community. The overall summary of all responses related to this survey is included in Figure 1.

Quality of life rating reported by participants with PD and care partners

Finally, the study included surveys about how PD impacted the QOL of participants with PD and the QOL of the care partners while caring for loved ones with PD. All participants with PD completed the PDQ-8 questionnaire [28], which included statements related to their mobility, activities of daily living, emotional well-being, social support, and cognitive and communicative functioning. Higher scores on the PDQ-8 are associated with poorer QOL. The average PDQ-8 score was 7.9, the standard deviation (SD) was 5.07 and the scores ranged between 0–19. There were three missing responses, and only 1 out of 27 participants reported a score of 0, suggesting no negative impact of PD on their functioning at the time of study participation.

The current study also examined the QOL of care partners. All participants completed the PDQ-Carer questionnaire [29] that addressed the mental implications of caring for an individual with PD. Higher scores on the PDQ-Carer are associated with poorer QOL. The average PDQ-Carer score was 24.6, the standard deviation (SD) was 16.5, and scores ranged between 4–38. Of the twelve care partners, five did not complete the questionnaire.

Relationships between participant’s variables and QOL scores

Based on the completed surveys, non-parametric Spearman correlations were completed to determine any relationships between the age of participants, gender of participants, self-reported depression scores, self-reported QOL scores, and self-reported PD severity for the PD participants alone. The alpha level of significance was .05. Specific to the PD group, significant positive correlations were observed between self-reported depression and QOL scores (r=0.504; p=0.012). In other words, all PD participants reported at least some level of depression.

Similar to the PD group, relationships for different variables related to the care partner group were also examined. However, no specific relationships were noted for these participant’s age, gender, self-reported depression, and QOL scores. It is important to note that the care partner group only had 11 participants, with seven who completed the PDQ-Carer questionnaire. The small sample size may have been attributed to the lack of a significant relationship between the different scores and participant’s demographic variables.

DISCUSSION

The present study examined the current perceptions of PD-related symptoms experienced by people living with PD and their primary care partners based in four states of the United States. Additionally, the study examined the current unmet needs of people with PD and their families.

Knowledge and perceptions of PD symptoms

The current study included a symptom checklist of PD with possible motor, non-motor, and communication changes based on previous literature [2,10,12,20]. Most PD and communication partner participants checked externally observable motor symptoms associated with PD in the current study. In contrast, these participants did not frequently report nonmotor and communication changes. The relatively lower reports of nonmotor symptoms by care partners agree with some prior studies. For example, approximately 67.6% of family members reported nocturia as a possible non-motor symptom of PD in the study [10]. However, only 17% of our study participants reported nocturia.

In addition, two other non-motor symptoms, constipation, and restless leg syndrome, were reported by more than two-thirds of the participants in the Cheon study [10]. While none of the care partners reported these symptoms in the current study. Lastly, in the Cheon study, restless leg syndrome was reported as one of the more prevalent nonmotor symptoms by 66.7% of family members [10]. Again, this starkly contrasted with the current study, where no care partners reported restless leg syndrome among their loved ones with PD.

It is possible that sometimes care partners may not be aware of some of the changes experienced by people with PD or may not associate these changes specifically with PD. However, it is important to note that only 25–42% of care partners reported these non-motor changes in their relatives with PD. In other words, more than half of the care partners did not report any nonmotor or communication changes in their loved ones with PD, which can suggest either these changes were not experienced by their loved ones with PD or the care partners were not aware of these changes to be directly linked with PD. In addition, methodological differences between the prior and current studies could explain some of the participant’s responses. Some of these differences included geographical location, sample size, the data collection format, the participant’s mean ages, and the structures of the perspective questionnaires used. In conclusion, the existing literature and the current study indicate the need for more widespread awareness and education about the nonmotor changes associated with PD among people with PD and their families.

Access to PD-related services

In addition to PD-related symptoms, all participants completed a survey to report access to PD-specific healthcare services. The PD-related services targeted physical, psychosocial, disease progression, and environmental adaptations. Results suggested that care partners and people with PD had similar reports of currently accessed healthcare services. Both participants reported pharmacy, neurology, and physical therapy are the most frequently accessed services. In addition, surveys indicated several services that target external and physical symptoms (gait, balance, voice) through physical therapy and voice therapy programs. The current study findings agree with prior studies. For example, Lageman and her colleagues [30]. Reported neurology (63.6%), pharmacy (43.9%), and physical therapy (30.3%) as the most utilized PD-related services in Virginia. In contrast, the participants did not have access to other services like the current study. In summary, physical and communication-related services were more readily available to participants with PD, while some of the neuropsychiatric and nonmotor symptom management, such as access to a psychiatrist, a sleep specialist, nutrition services, counseling, and end-of-life care-related services, were often lacking for many people with PD in the current study.

Unmet needs of the PD community

The study also analyzed the unmet needs related to PD. The multitude of needs was categorized by various daily and long-term effects of PD, including symptom management, lifestyle changes, emotional changes, and other related changes. Approximately 30% of PD participants expressed a need for planning for the future, wellness strategies, and lifestyle changes. Although most participants reported resources related to the early onset of PD diagnosis to be met, a large percentage of participants with PD and care partners reported symptom management, planning for the future, and resources aimed at emotional and cognitive changes to be some of their commonly unmet areas of need. Based on the available results, it can be concluded that both participants with PD and their family members expressed a lack of resources to effectively manage symptoms and help adjust one’s daily functioning following a PD diagnosis.

There were some overlapping themes between the current study based in Texas and Oklahoma, with a prior study by Hatano et al [12] related to participants in Tokyo. While the participants in the earlier study by Hatano et al. [12] reported measures for adverse situations and pharmaceutical treatments to be some of the unmet needs, the current study indicated that care partners would also like to have more information and resources centering on emotional and familial changes, future planning, and symptom management. Overall, the current study provided a snapshot of some of the unmet needs in these communities.

It is important to note that some of the services reported to be lacking more than a decade ago are becoming more available in the current times. For example, Buetow et al. [11] reported in 2008 that 16.8% of their participants with PD had never seen a physiotherapist, 13.9% had never seen a dietician, and 13.4% had never seen an occupational therapist. In contrast, such services are more readily available now as more than half of the PD participants and more than 30% of care partners in the current study reported having access to or participating in physical therapy or exercise groups. This indicates that availability and access to some therapy services have improved in recent years in rural communities in the United States, such as Oklahoma and Texas. However, other essential services are still lacking as most participants with PD reported unmet needs related to services to help adjust one’s lifestyle secondary to PD and helpful resources to plan.

Although PD is known to affect multiple modalities, there is presently a strong unmet need for services for non-motor symptoms. Specifically, care partners reported not having access to sleep specialists, psychology/counseling, neuropsychology, nutrition, clinical trials/research studies, social work, and palliative care to address their family member’s PD needs. In addition, participants with PD and their care partners shared similar concerns about the lack of access to services to manage different non-motor symptoms effectively. Overall, the current study indicated the need for more specialized services for nonmotor changes related to PD. These findings concur with prior studies completed during the last 13 years, like Dobkin et al. [31] and Hatano et al. [12], who reported a need for mental health services among their participants with PD. Thus, healthcare professionals must collaborate with different support groups, community organizations, and social workers to create programs related to these areas for people with PD and their families.

Like Lageman et al. [30], the present study reported the need for mental health resources for the PD communities. In the Lageman et al. [30] study, 10.6% of the participants reported a need for counseling and psychiatric services in Virginia (located in the southern region of the United States). Additionally, 24.2% of the participants reported a lack of specialists and services in their local area. The current study showed that about 15–22% of study participants reported inadequate support to manage stress, anxiety, and other mental health concerns.

In conclusion, the current study is informative as it aids in understanding the current perceptions and experiences of the PD communities within the United States. However, there is a critical need to provide education and resources to these communities, including access to MDS, neurological services, physical therapists, nutritional services, clinical trial information, and home-health-related services.

Quality of life of participants

The current study also asked participants with PD about their impact on their QOL. As PD is a multimodality disorder, understanding how it impacts the QOL of the PD community is important. The scores for PDQ-8 range from 0 to 32, with higher scores indicating poorer QOL. All 27 participants with PD indicated at least some impact of PD symptoms on their QOL. In addition, the current study indicated a positive relationship between depression and QOL scores. People who self-reported depression also had poorer QOL. These findings agree with Dobkin et al.’s [31] and Marsh’s [32] studies. Conclusively, the current study confirms the existing literature about the possible impact of depression on the QOL of people with PD.

Clinical implications

The present study provided information regarding symptoms and current met and unmet needs experienced by the PD community. Specific to the symptoms experienced, more treatments must be provided to manage the mental and nonmotor symptoms of people with PD. In addition, increasing the availability of resources that improve and address mental health concerns, such as depression and anxiety, can be critical for people based in the four states of the United States. Also, providing better awareness and education about nonmotor symptoms during medical visits and different healthcare services and resources can have long-term implications for newly diagnosed and those with existing diagnoses of PD. Further, increased information and access to specialists who help with all PD modalities can benefit the PD communities. Finally, providing education about available resources about PD and their possible benefits can benefit communities.

Study limitations

Throughout the time frame of data collection, a global pandemic (i.e., COVID-19) limited participant recruitment to a large extent. In addition, due to the Centers for Disease Control guidelines, only online outreach and participation were accessible, limiting participant responses compared to if the surveys were administered on paper and online. Finally, the study surveys were shared with participants via Qualtrics. However, some survey questions did not appear on the participant’s end due to unexpected technical glitches, leading to missing responses for some participants.

CONCLUSION

Based on the current findings, several future directions and areas of improvement were identified that are likely to impact the PD community in the United States and worldwide. Knowledge about PD and access to PD-related services can be addressed through providing information to new and those with an existing diagnosis of PD patients during routine medical appointments, community-based education programs, and distribution of factsheets and brochures about PD in different PD support groups. In addition, future studies with larger sample sizes involving people with different severities of PD and disease durations can clarify the current perceptions and experiences of the PD community. Further, due to the formatting of the survey, participants were not required to select the details of their actual residential communities and zip codes. Therefore, future studies can include questions specific to their primary residential region and current location to minimize any discrepancies in the geographical location of the participants.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The current study was supported by the Parkinson’s Foundation Community Engagement Grant (PF-CGP_2044), awarded to the first author.